Author: Nistha Sinha, 2nd year student at Symbiosis Law School, Pune.

Introduction

Cinema or films are an expression and a unique art form that has been widely popular in India even before independence. The origins of cinema in India range back to the beginning of the era of film itself. Commercial cinematography became a worldwide sensation after the premier of the Lumière and Robert Paul moving pictures in London (1896)[1] following which, by mid-1896 both had been screened in Bombay[2]. As a visual medium, films and serials are widely popular all over India, with content being created in myriad Indian languages, across all states.

In this particular case, the Supreme Court of India noted the powerful and strong impact that motion pictures have on the audience. It engages the spectator on several levels i.e., the visual and aural sense. The Court also acknowledged that television now had a much broader outreach in terms of how over the years it has been able to reach the most remote corners of the nation. Its strength is derived from the fact that it caters to not just the sophisticated, literate or educated but also to the masses of people who do not fall into that category and are living in distant villages. But, the Supreme Court also stressed that this means that the output of these motion pictures is capable of as much good as evil. It has already been established that films can stir up certain feelings in the viewer. The interaction between these motion pictures and its audience apart from what every individual may grasp from it may drastically vary from person to person. Hence, situations of conflict arising from this medium can be very dicey to handle.

Since the evolution of cinematograph technology; law makers, courts and jurists deemed it necessary that there needed to be a mechanism in order to ensure that a system of review and certification could be maintained. They were of the opinion that films have the capacity to impact the minds of the people unlike any other form of expression. Owing to this significant ability of cinematograph technology to influence and impact human minds, public exhibition of films was and continues to be, conditioned on prior censorship. Although, censorship can have both negative and positive connotations. The objective of such restrictions before permitting exhibition has obviously been justified as to restrain film expression in the interests of sovereignty, public order, decency, and to limit detrimental effects of such expression on the public. This, however, may often give rise to an opportunity for clash with the scope of fundamental right i.e. freedom of speech and expression. Technically, the only way in which these can be diluted are when the consequences are proved to be detrimental to national, public or social interest.The Courts have always opined that any imposition of restrictions must normally be reasonable, and must fit into the permissible limitations that may be placed on the expression under the Constitution.[3]

In furtherance of the need to review and certify content, the Cinematograph Act (1952) was introduced. This Act lays down circumstances under which such restrictions may be placed while certifying films for exhibition. A regulatory body called the Central Board of Film Certification (“CBFC”) was constituted under the Act to handle the task of reviewing and examining films to certify them as U (Universal Viewing), U/A (Parental Guidance), A (Adult Viewing only), and S (restricted viewing). Within the ambit of the powers of this body also lies the authority to reject a certificate if it is unfit for public exhibition.[4]

The issuance or rejection of the certificate depends on the review of the film by an examining body. Sometimes it can also be put through the scrutiny of a revising body of CBFC. Depending on the review of the film, issuance of the certificate may require excisions (“cuts”) or modifications to the film as per the suggestions of the CBFC.[5] The suggested changes are usually requested based on the principles and guidelines that have been included under the Act and Rules. Although it is to be noted that this decision by the CBFC can be appealed to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (“FCAT”), whilst also having the option to be challenged before the higher judiciary open under the writ jurisdiction.[6] The Act, its Rules and guidelines guide the way for the CBFC in the process of reviewing films.

Essential details of the Case

Citation: Ramesh S/O Chotalal Dalal vs. Union Of India & Ors., 1988 AIR 775, 1988 SCR (2)1011

Petitioner(s): Ramesh S/O Chotalal Dalal

Respondent(s): Union of India & Ors.

Petitioner’s Lawyer: Dr. Y.S. Chitale, Dr. N.M. Ghatate and S.V. Deshpande

Respondent’s Lawyer: Kuldeep Singh (Additional Solicitor General), Soli J. Sorabjee, Parimal K. Shroff, P.H. Parekh, Sanjay Bhartari and Miss A. Subhashini

Concerned Statutes and Provisions: Cinematograph Act (1952) – Sections 3, 4, 4A, 5 and 5A to 5D; Articles 21 and 25 of the Constitution

Bench: Sabyasachi Mukharji, S. Ranganathan

Date of Judgment: 16th February, 1988.

Present Status: Case dismissed.

Facts of the Case

‘Tamas’ was a television serial that was created basing its storyline on a book written by Shri Bhisham Sahni. Before the petitioner moved the Court, four episodes had already aired on television. The applicant’s petition to the Court was made under Article 32 of the Constitution. The applicant’s plea was for a writ of Prohibition or any other appropriate order restricting the makers of the show from telecasting or further screening the serial. The petition also highlighted that the petitioner wanted to enforce their fundamental rights under the Constitution meanwhile declaring the screening or televising of “Tamas” as a violation of Section 5B of the Cinematograph Act, 1952.

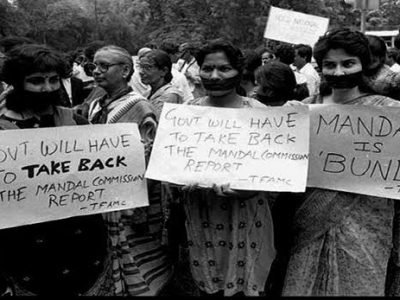

“Tamas” is a story of partition of India depicting the plight of Hindu and Sikh families crossing over into the present day independent India. It was a tragedy for mankind, a significant turning point and heartbreaking tale of displacement and loss across the sub-continent. There is obviously unpleasant and uncomfortable portrayal of the sufferings of those caught at crossroads during partition. Today the serial is hailed as part of the ‘parallel cinema movement’ of the Seventies and Eighties in India and has also received critical acclaim for its raw portrayal of the realities of partition.[7] In their petition, the reasoning was stated to be that the exhibition of the said serial would be against public order and could potentially wreak havoc whilst also inciting the people to indulge in the commission of offences. Therefore, it should be considered to be violative of Section 5B(1) of the Cinematograph Act, 1952 (hereinafter called ‘the Act’) apart from destroying the principle enshrined under Article 25 of the Constitution[8]. Another contention in this matter is that it is also violative of Section 153A[9] of the Indian Penal Code and the show was further accused of portraying prejudice towards national integration.

Prior to this, there had been a writ that was admitted into the High Court of Bombay. Mr. Javed Ahmed Siddique had filed the said writ petition[10]. Henceforth, it was granted an interim stay which was later challenged by the respondents. It was thus vacated by a Division Bench of the High Court, on appeal. This decision was made based on the experience of the Bench after viewing the complete serial. A special leave petition was then filed against that judgment.

The depiction of the Hindu-Muslim and Sikh-Muslim strife during the partition of India which included visuals of killings and looting in the serial lead to the understanding of the judgment by the Bench.

Later however, the Bombay High Court bench overruled the interim order. The screening of Govind Nihalani’s imaginative, “impassioned and impartial documentation of the virus of communalism was permitted”.[11] Protests by the Shiv Sena and the Bharatiya Janata Yuv Morcha broke out and followed suit, and Siddiqui said he would appeal to the Supreme Court.

In the opinion of the Bench, “the serial inter alia depicts how communal violence was generated by fundamentalists and extremists in both communities, how innocent persons were duped into serving the ulterior purpose of fundamentalists, and how extremist elements infused tension and hatred for their own ends”.

The ruling in favour of Tamas by the judges had its basis around the fact that the content attacked fundamentalists or extremism in both communities equally. Further, the bench also highlighted how at the end of the day, the show was really about brotherhood beyond religion.

The serial was granted ‘U’ certification by the Central Board of Film Censor. In this judgment, the Supreme Court of India therefore felt that provisions of the Cinematograph Act, 1952, were very relevant. The Court revisited some of the sections that could potentially provide a clear lens for this case. The judgment cited the following sections of the Act:

- Section 3 of the Act[12] provides for the Board of Film Censors.

- Section 4 of the Act[13] provides for examination of films. The examination in the first round is done by an Examining Committee under section 4A.

- Section 5[14] states that under certain circumstances, it is examined by a Revising Committee . The expected outcome from the Committees are not only their recommendations but also the clear reasons in cases there is difference of opinion within the Committee.

Section 5A of the Act states that on further examination of the film in a prescribed manner, if the Board regards that the film to be suitable for unrestricted public exhibition, a ‘U’ certificate is given to it. Section 5B of the Act is in regards to guidance in certifying films. Section 5C of the Cinematograph Act has provisions for the creation of Appellate Tribunals. These tribunals would consist of persons who are familiar with the social, cultural or political rubric of India apart from having special knowledge of the myriad regions of India. In addition to this, the members also require special knowledge of films and their impact on society, to hear appeals from the orders of the Censor Board. Further, according to section 5D, the Tribunal has the power to hear appeals by people who, having applied for a certification of a film, are aggrieved by a Board order refusing to grant a certificate or granting a restricted certificate or directing the appellant to carry out certain excisions or modifications to the film. Sub- section 5 of section 6 is a fresh addition to the Act which highlights the Central Government’s revisional power in respect of a film certificated by the Appellate Tribunal.

Issues

- Whether creative forms of expression like “Tamas” are subject to morality?

- Whether the impugned sections of the Cinematograph Act is violative of Fundamental Rights?

Arguments from Petitioners

- Highlighted that the telecast of the serial would be a hindrance to public order and had the potential to incite violence amongst the people and encourage masses to indulge in the commission of offences. Therefore it was deemed violative of section 5B(1) of the Cinematograph Act (1952) and also was against the principles enshrined under Article 25.

- It was touted to be very prone to promoting feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will amongst the religious groups that found themselves fictitiously portrayed in the serial.

- Also, the petitioners contended that it was prejudicial to communal harmony and national integration, which would make it an offence under section 153A of the Indian Penal Code;

- The petitioners argued that there was a high chance that the portrayal of events and characters would most likely not just provoke but also instigate people of all ages exposed to it. Therefore, the viewership would fail to grasp the message if any behind the serial.

- Further, the petitioners argued the concept of how the raw truth is not always and under all circumstances considered to be desirable for display or exhibition.

- Lastly, the petitioners brought to light how the Judges’ perspective, who having viewed the film from their own point of view, is for a fact more evolved and modern while the average viewer in the country (at that time) could not be considered as sober and experienced as the Judges of the High Court.

Arguments from Respondents

- The Respondents on the other hand argued on the basis of the fact that prior to this the serial went through the required procedure of clearance.

- It was also highlighted that all the appropriate authorities had taken the film into consideration and had found it acceptable for unrestricted public exhibition.

- Further, the respondents raised that the only question is whether the film has been misjudged or viewed from the wrong lens or perspective and also whether it was allowed to be exhibited or serialised on a wrong approach.

- The film depicts violence without a doubt, the respondents agreed to it but the point that they stressed on was that the violence portrayed in the serial between the communities took place before the pre-partition days. Therefore, it was fiction based on fact and the truth.

Judgment Held

- The Cinematograph Act is equipped and contains provisions to maintain the sensitivities of the public.

- There must be trust on the approval given by the Examining Committee.

- The correct approach according to the Court was to read the book or view the serial from the perspective of an ordinary man.

- The division bench’s finding highlighted that the takeaway from the serial by viewers could be entirely peaceful and that the serial just portrayed raw history through a lens.

- The Court did not find any violation of Art. 21 and Art. 25, further stating that there was no perceived danger to communal harmony.

Judgment Reasoning and Analysis

From the overall perspective of the serial, it was held that it cannot be considered to be in either violation of any clauses of the Cinematograph Act or the resulting violation of the fundamental rights of the petitioner.

The judgment highlighted the competency of The Cinematograph Act in respect to the provisions laid out in the sections mentioned in this judgment. The Court went on to further elucidate that no authority would give a free pass to screen anything that is likely to offend or hurt the religious sentiments of the viewers. The judgment further went on to stress how the legislation itself was quite intricately designed and elaborate apart from the great competency of the examining committee. It was a necessary detail in the judgment because the judiciary did not want to create confusion over the competence of a specifically constituted body.

The Court also held up creative liberty by being very coy and matter of fact about reading the book for reference and viewing the serial as it should be and not adding too much unnecessary meaning to it. Further, the judges having viewed the film consciously made it a point to view from the ordinary viewer’s perspective. Their afterthoughts reflected that the serial was only a representation of history and found no damage in portraying bare facts in an objective manner. They also commented on how the serial’s portrayal of fundamentalism and extremism would help the public opinion evolve over time. The judiciary appreciating and encouraging creative liberty and expression was a very progressive step in the 1980s, making this a landmark judgement in media and entertainment law.

The judgment focussed on reasonability and rationality which are fundamental to art and expression as they are usually subject to individual perspective and quite abstract in nature. The judgment stressed on the final message that was received from viewing the serial and how they found no evidence supporting the claims of the petitioners.

References

[1] The Lumiere Brothers: Pioneers of Cinema and Colour Photography, NATIONAL SCIENCE AND MEDIA MUSEUM (Jun. 10, 2009), https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/the-lumiere-brothers-pioneers-of-cinema-and-colour-photography.

[2] Uday Bhatia, 120 years of watching movies: the first picture show, MINT (Feb. 22, 2017, 01.09PM), https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/YovgiRxYBwmx9yo54M1scL/120-years-of-watching-movies-The-first-picture-show.html.

[3] S. Rangarajan Etc vs P. Jagjivan Ram,1989 SCR (2) 204, 1989 SCC (2) 574.

[4] The Cinematograph Act, 1952, § 5A, No. 37, Acts of Parliament, 1952 (India).

[5] The Cinematograph Act, 1952, § 5B, No. 37, Acts of Parliament, 1952 (India).

[6] The Cinematograph Act, 1952, § 5C, No. 37, Acts of Parliament, 1952 (India).

[7] Poonam Saxena, Tamas: A genuine television classic, HINDUSTAN TIMES (Aug. 16, 2013, 10.17PM), https://www.hindustantimes.com/entertainment/tv.

[8] INDIA CONST. art. 25

[9] The Indian Penal Code, 1860, § 153A, No. 45, Acts of Parliament, 1860 (India)

[10] Writ Petition No. No. 201 of 1988

[11] Salil Tripathi, Tamas: Govind Nihalani’s serial on Partition rises religious protests, INDIA TODAY (Feb. 15, 1988, 12.07AM), https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/indiascope/story/19880215-tamas-govind-nihalanis-serial-on-partition-rises-religious-protests-796914-1988-02-15.

[12] The Cinematograph Act, 1952, § 3, No. 37, Acts of Parliament, 1952 (India)

[13] The Cinematograph Act, 1952, § 4, No. 37, Acts of Parliament, 1952 (India)

[14] The Cinematograph Act, 1952, §5, No. 37, Acts of Parliament, 1952 (India)